Kelsey Mann felt a little anxious when he was called to an unexpected meeting with Pixar bosses late in 2019.

But rather than something bad, the meeting turned out to be an invitation to come up with ideas for a possible sequel to one of the company’s most successful and acclaimed features. And anxiety turned out to be the key to Mann’s concept for Inside Out 2.

“I wanted to do a story that dealt with anxiety and not feeling good enough,” says Mann, who over 15 years at Pixar has earned story supervisor or writer credits on Monsters University, The Good Dinosaur, Onward and other projects from the Disney-owned animation studio. “That self-conscious feeling you get when you’re a teenager, when you start to compare yourself to others.”

The original film — a 2016 animated feature Oscar winner directed by Pete Docter before he became Pixar’s chief creative officer — was a coming-of-age tale that cleverly took audiences inside the mental ‘headquarters’ of 11-year-old girl Riley, where five personified emotions, led by the ever-upbeat Joy, tried to negotiate the challenges posed when Riley’s family moved to a new city.

The follow-up, on which Mann makes his feature-directing debut and has a story credit, finds Riley at 13, a happy teen who is about to be hit by the emotional maelstrom of puberty. Things come to a head (so to speak) during a fraught ice hockey training camp, where choosing between old and new friends creates havoc among Riley’s emotions.

To simulate the tumult of the adolescent mind, Mann initially came up with a slew of new emotions — among them Schadenfreude, Surprise and Shame — to join the first film’s Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear and Disgust in Riley’s head. He reconsidered, however, when the project, following Pixar’s famed iterative production process, went through the first of its multiple rough-draft screenings.

“I wanted to overwhelm Joy and the old emotions with all this chaos,” explains the director. “So I flooded headquarters with all kinds of new emotions. And I not only overwhelmed Joy, I overwhelmed the audience. The first note I got on the first screening was ‘simplify’. So we cut the new emotions down from nine to four.”

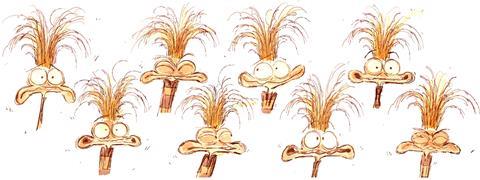

Design progression

The new emotions/characters that made the cut — painfully shy giant Embarrassment, French-accented Ennui, perpetually jealous Envy and frazzled Anxiety — went through their own development process.

Anxiety, who for much of the story serves as the antagonist to lead character Joy, started out “a little more monstrous”, recalls Meg LeFauve, a screenwriter on the first film who returned for the sequel and shares story credit with Mann. “We tried that, but it didn’t feel authentic to our own experience of anxiety. She was a baddie for a while, but again it didn’t feel authentic. It kept coming back to the fact she has a good goal but a bad plan.”

The hard part, says the sequel’s other screenwriter Dave Holstein, was in “figuring out how you paint Anxiety in such a way that she’s still a threat and working against [Joy] but ultimately they can dovetail”.

In addition to developing the characters, the writers (who worked on the project consecutively rather than together) had to juggle the film’s three main storylines: one for Joy, one for Riley and one for Anxiety. “It’s like three-dimensional chess,” says LeFauve.

Anxiety was also a challenge for the design team. “She went through a lot of changes,” says Mann of the character, emerging with an abstract look dominated by a gaping, toothy mouth and a pair of bulging eyeballs.

In the first film, male characters Fear and Anger are “more pushed in terms of design, more stylised”, notes Mann, “and the women aren’t pushed as far. Jason Deamer, our production designer, wanted to have Anxiety be a female character that was as pushed a design as Fear. I love how playful her design is and how pushed she is. She’s my favourite, because it was so difficult to achieve the final look.”

In structuring the sequel’s story, Mann made a list of his favourite sequels and those he considered less creatively successful, “and the ones I liked explored new worlds that I didn’t even know were there”. So for his story, “I knew I would want to explore new areas in the mind that I didn’t know were there but were just around the corner in the first film.”

That resulted in a journey to the back of Riley’s mind that has the emotions passing through an expanded version of the first film’s Imagination Land (now including Anxiety’s team of workers busily creating worst-case scenarios), crossing the teen-inspired Sar-chasm, and doing time in The Vault, a new location where Riley’s secrets are kept safely hidden.

Casting the sequel involved another blend of the familiar and the new. Amy Poehler returned from the original film to voice Joy, along with stand-up comedian Lewis Black as Anger and Phyllis Smith (from the US version of The Office) as Sadness.

Mindy Kaling and Bill Hader, however, did not reprise their roles from the first film, reportedly because of pay disputes. Tony Hale, from Veep and Toy Story 4, took over as Fear and Liza Lapira, from Fast & Furious, as Disgust. The buzzy talents cast in the film’s new roles included Maya Hawke as Anxiety, Ayo Edebiri as Envy, Paul Walter Hauser as Embarrassment, Adele Exarchopoulos as Ennui and June Squibb as the briefly glimpsed Nostalgia.

With the nine-year gap between original film and sequel reducing the likelihood of direct comparisons by audiences, “we weren’t looking to match voices” in recasting Kaling and Hader’s roles, says Inside Out 2 producer Mark Nielsen, a 28-year Pixar veteran who was a producer on Toy Story 4 and an associate producer on Inside Out. “We were looking for great actors who could bring a lot of improv, bring the comedy and the dramatic heft to these roles, but could also tap into that emotion and carry it in a way that you felt you were listening to fear and disgust.”

When it came to capturing the voices, the project was able to complete most of its recording sessions before the July start of last year’s US actors strike, Nielsen reports — so “aside from a few additional lines we needed to re-record here and there, the strike did not impact our overall production too much”.

Technological leap

While it may have helped with casting, the lag between Inside Out and its sequel added to the technical challenges that cutting-edge Pixar projects often encounter. “Technology changed dramatically over those nine years,” explains Nielsen. “The shading and lighting tools that we use now are completely different, so we were not able to just reuse the characters and the sets from the first film. It took about a year before our technology teams had a version of Joy that looked comparably good to the first film.”

The 2D characters — Riley’s childhood cartoon favourites — which appear in The Vault, meanwhile, were a tricky departure for a 3D project. “It was actually harder to do something like that in the Pixar pipeline,” says Mann. “Anything that’s outside the [Pixar] norms is a little difficult, because it’s a whole new pipeline.”

And the sequel’s climactic panic-attack sequence was “probably the most complicated thing we did”, the director adds. “Anxiety is flashing all over the place, with a tornado effect happening behind her. That took a ton of work to get right.”

Eventually, of course, the challenges were met over a four-year schedule — slightly shorter than Pixar’s four-to-five-year average — that took in nine versions of the film, each of which was screened for the studio’s vaunted brain trust of in-house filmmakers as well as for psychology experts and a group of teenage girls from around the US (see sidebar).

The work paid off when Disney launched Inside Out 2 in June 2024 with an opening weekend worldwide gross of $295m. By the end of the summer it had amassed nearly $1.7bn, making it 2024’s biggest hit and the highest-grossing animated feature of all time (eclipsing Disney’s 2019 photo-realistic remake of The Lion King). Its awards nominations include two at the Golden Globes and seven at the Annies.

Fans of the Inside Out world can now spend more time with its characters — plus some new inhabitants — in Dream Productions, a recently-launched Disney+ streaming miniseries, produced by Pixar, about the ‘studio’ in Riley’s head that stages her dreams.

But whether fans will get to take another big-screen visit to the world remains to be seen. At last year’s D23 Disney fan event in August, company CEO Bob Iger seemed to hint at another entry, saying in a TV interview that he “would love” to see an Inside Out 3.

Kelsey Mann, however, says he knows of “no current plans” for a third film. He concedes, though, that “a lot of people want that, and a lot of people asked about that before this movie even came out. People just want to see Riley’s whole life.” Ns

Riley’s Crew: Inside Out 2’s teenage girl focus group

Research and focus groups are part of Pixar’s process for developing features, but with Inside Out 2, the studio sought input from some uniquely qualified experts. Through referrals from organisations and studio employees, the project put together a group of nine girls aged at the time between 13 and 16 and hailing from the US states of California, Washington and Louisiana.

Dubbed ‘Riley’s Crew’ after the film’s central human character, the group was shown each rough cut of the sequel over a three-and-a-half-year period. And after each screening, the girls — who only met face-to-face when they were invited to the film’s Hollywood premiere — gave their feedback to filmmakers in a Zoom meeting.

“We wanted to make sure this was resonating with teenagers now,” says Inside Out 2 producer Mark Nielsen, regarding how the production used the Crew’s input. “We wanted them to weigh in on our representation of Riley and her friend group, how she’s feeling and the emotions she’s wrestling with.”

The girls were sometimes shy about criticising the filmmakers’ work, says sequel screenwriter Meg LeFauve: “But often it was them saying, ‘I feel that way. That feels right to me.’ Which is super-important to know.”

For scientific pointers, the project turned to Dacher Keltner, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley’s psychology department, and Lisa Damour, a clinical psychologist who has written books about teenagers’ emotional lives.

The idea, explains Nielsen, was “to help keep us honest with what’s going on in the mind. Anxiety exists for a very important reason — it’s there to help you. So we wanted to make sure we did justice to the emotions and the way we represented them, even when you need some of them to be a little bit of an antagonist in the story.”

Director Kelsey Mann recalls meeting with Keltner, who also served as a consultant on the original film, during his first week working on the sequel. “I asked him what happens in the brain when we become teenagers,” he says. “He leaned back in his chair and said, ‘Oh my goodness Kelsey, it’s a lot. Where do I begin?’ That made me excited, because it felt like there was something substantial there.”

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet