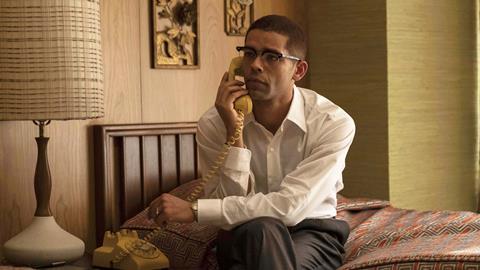

Kingsley Ben-Adir faced the challenge of his life after winning the role of Malcolm X in Regina King’s ‘One Night In Miami’. Screen talks to the UK actor about playing an American icon.

When Kingsley Ben-Adir was invited to self-tape for director Regina King’s One Night In Miami, adapted by Kemp Powers from his own stage play, the London-born actor was naturally thankful for the opportunity. But he still turned it down.

Over the course of two years, Ben‑Adir had been through a lengthy process of auditioning, screen-testing and training to play Muhammad Ali in Ang Lee’s still-unmade film about the boxer’s 1975 fight with Joe Frazier in the Philippines, Thrilla In Manila. Now King was inviting him to read for the role of Ali again — except for events that occurred 11 years earlier, when the boxer, then known as Cassius Clay, was aged just 22.

One Night In Miami offered four powerful roles in its story of four African-American men, all legends in their own right — politician Malcolm X, musician Sam Cooke, American football star Jim Brown, and Clay — who meet up in a Miami hotel room in February 1964, the same night Clay wins the world heavyweight title from Sonny Liston.

“My team were very, very excited,” recalls Ben-Adir, who was hitherto best known for TV work including The OA, Peaky Blinders and High Fidelity, and is repped out of Los Angeles by a trio of agents at CAA and two managers at Range Media Partners. “There was a huge buzz around the script, and everyone was auditioning for it. There are so many scripts that just go straight to offer, so for working actors, you never see them. But this was one of the rare instances where — and that’s down to Regina and her openness and curiosity — she wanted to see everyone and to give everyone a chance to put their foot forward.”

Ben-Adir felt he was not right to play Ali at such a young age, and passed up the opportunity “much to everyone’s confusion”. However, he had his eye on a different role.

“I did say, if anything happens with Malcolm, I would love to audition,” he recalls. “Because there’s something about Malcolm in this movie that just felt different and gentle and interior. The debate between him and Sam was electric on the page. I was like, ‘Oh, this is where the meat is. This is where, for me personally, as an actor, I’m going to be able to fully engage, and I’m going to be curious and stimulated and challenged.’ I never thought it was going to come, but cut to six months later, Malcolm did become available.”

High stakes

Ben-Adir submitted a tape, and that same evening he was speaking to King — an Oscar winner in 2019 for her role in If Beale Street Could Talk, following a screen acting career beginning in 1985, and whose previous directing credits have mainly been for television. Over the next two weeks, he and the director spoke for “at least 10 hours on the phone”, and he also talked with Aldis Hodge, who had been cast as Jim Brown. “They were really putting it to me,” he recalls. “They really wanted to make sure I understood the magnitude and the stakes of what we were about to shoot, so I had to spend a bit of time to convince them that I really did.”

There was just one snag: production on One Night In Miami was already fast approaching. “I had to lose 20 pounds in no time at all,” says Ben-Adir. “I had about 105 pages of text to learn and a dialect, and to understand the whole of Malcolm’s existence in, like, a couple of weeks.”

But when he arrived on the New Orleans set in January 2020, the actor turned the situation to his advantage. In the film, Malcolm finds himself at a crossroads in his life: despite wooing Clay to embrace the Nation of Islam and announce himself as Muhammad Ali, he himself is on the way out, and his relationship with the group’s leader Elijah Muhammad had already fractured.

“I think there’s something about the pressure that I was under personally that was helpful,” he says. “That helped bleed into the pressure and the stakes that Malcolm…” The actor immediately interrupts himself. “I’m not comparing them at all. But something about that state of being wired, constantly, for two months that I think really helped my energy. There was a forthrightness that I came in with every day in terms of how I was going to play it that was unapologetic, and determined. I think we all kind of fell into our characters naturally.”

Now all four actors are in the running for awards, with Ben-Adir and Eli Goree (as Clay) submitted in the lead actor category, and Hodge and Leslie Odom Jr (as Cooke) in supporting. (The Golden Globes have decreed all the performances will run in supporting actor.)

Adding to the pressure on Ben‑Adir during filming was that he was already committed to shoot his role as Barack Obama in the Billy Ray-created miniseries The Comey Rule — which meant flying to Toronto while King shot a sequence where Cooke and Clay leave Malcolm’s hotel room for a celebratory visit to the Copacabana club.

Put another way, Ben-Adir was performing as two African American icons at the same time — a fact that has raised eyebrows in the US, where there is concern about black British actors seemingly depriving their US counterparts of roles.

The actor addressed this topic when interviewed by the Los Angeles Times last August, a month after Amazon Studios acquired One Night In Miami, and a month before its Venice Film Festival premiere. Asked if he was prepared for a backlash, his reply — suggesting that US stars such as Samuel L Jackson perhaps did not understand “what it’s like growing up as a black man in inner-city London” — led to a storm on social media.

Talking to Screen International, Ben-Adir is understandably keen to put that particular controversy behind him. “I really want to make sure this is a moment to celebrate the film. I want to make sure the attention is on that, and not unnecessarily towards me, because it feels irresponsible.”

Nor does the actor wish to dwell on the fact many of his best screen-acting opportunities have come from the US, and that he has chosen not to have any representation in the UK. He does, however, acknowledge he has now started to receive better opportunities to work in his home country. “I always understood that, for good or bad, a big project like this in America changes the discourse when you come back [home]. And that’s immediately started happening.

“Rather than it seeming like I’ve had to go to America to get success, and how unfair is that? No. That’s what you knew it was going to take. To now be able to come back here and have conversations with producers and directors about the projects that I want to develop and get off the ground is incredible.”

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet