While UK and Irish films have long struggled for traction at the major European festivals Berlin, Cannes and Venice, this year’s Toronto International Film Festival is typically awash with them.

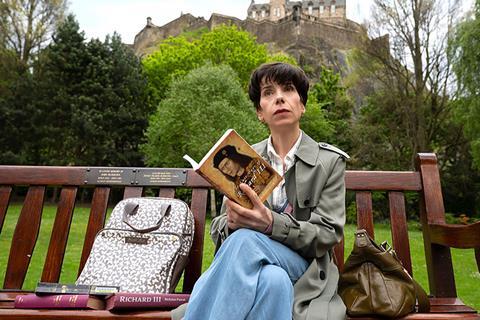

World premieres at TIFF include Sally El Hosaini’s opening night film The Swimmers; Richard Eyre’s Allelujah, a drama about old age featuring Judi Dench; Lena Dunham’s 13th-century set Catherine Called Birdy; Frances O’Connor’s Emily Brontë biopic Emily; Shekhar Kapur’s cross-cultural romantic comedy What’s Love Got To Do With It?; Stephen Frears’ The Lost King starring Sally Hawkins as a historian looking for the remains of King Richard III; Mary Harron’s closing night film Daliland, a UK-US co-production; and Michael Grandage’s My Policeman starring pop star Harry Styles as a gay policeman in 1950s Brighton.

Also joining the TIFF fray following premieres in Telluride and/or Venice are Joanna Hogg’s mystery drama The Eternal Daughter starring Tilda Swinton, Florian Zeller’s The Son, Martin McDonagh’s The Banshees Of Inisherin, Sam Mendes’s Empire Of Light and Sebastian Lelio’s The Wonder, all of which are UK productions or co-productions.

The robust presence for UK films at Toronto in part reflects an ongoing boom period for production in the UK. Inflation, corporate restructuring (including Warner Bros’ merger with Discovery) and the cost-of-

living crisis have not dampened the desire among the streamers and US studios to work in the UK, with the demand for studio space and crew at voracious levels according to the British Film Commission.

Multiple financing sources

A key player at TIFF this year is UK production powerhouse Working Title Films, which has a long-term first-look arrangement with Universal Pictures. In a sign of the times, however, its three films at this year’s festival are each with three different partners, two of them streamers: The Swimmers is a Netflix title, Catherine Called Birdy is with Prime Video and What’s Love Got To Do With It? belongs to Studiocanal.

It suggests that for established UK producers such as Working Title co-heads Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner, there are now multiple sources of financing and distribution to tap outside the legacy studios. New players are also entering the UK fray — earlier this year, A24 hired away two high-profile BBC executives to set up a UK division: director of drama Piers Wenger and BBC Film head Rose Garnett (Allelujah and The Lost King both have BBC Film involvement).

Strictly using the TIFF line-up as evidence, it points to a golden age, at least for mid-range UK cinema. That is not, however, how it appears from the ground. In July, the British Film Institute issued a report, An Economic Review Of UK Independent Film, that revealed deep anxiety across the sector about the parlous state of indie production.

“The truth is that, right now, there is an imbalance in the ecosystem which is provoked by the streamers,” argues Cameron McCracken, managing director of Pathé UK, which backed Eyre’s Allelujah and Frears’ The Lost King. “There is a disconnect between the soaring cost of making films, because it [the sector] is overheated with the huge volume of production being undertaken by the streamers who operate in a totally different market to the independents.”

With the likes of Netflix, Amazon, HBO and Disney occupying UK soundstages and snapping up crew and talent, there can only be one end result — prices have been driven up and created a skills shortage that is reaching crisis levels. Meanwhile, the value of UK independent films in the international marketplace is falling. “The model is broken,” McCracken acknowledges. “The international sales forecast that I will do with the sales teams — these valuations on the minimums which is how you assess the collateral for your investments, what the German distributor will pay, what the French distributor will pay — is falling.”

It is also noticeable the TIFF films are mainly from familiar directors and seasoned producers, rather than rising talents. “Those movies would always get made,” says Damian Jones, a producer on Allelujah, of this year’s TIFF harvest. “It’s the smaller, more left-of-centre ones — perhaps not overtly commercial but that turn into great movies — that are currently much harder to make.”

Conspicuously, smaller, edgier UK titles in the mould of Lady Macbeth and Beast — which made a splash at Toronto in recent years in the competitive Platform section — are not in the selection (apart from Basil Khalil’s Palestine-UK production A Gaza Weekend, which plays in Discovery). Cora Palfrey, a producer of My Policeman and COO at UK sales and production outfit Independent, says it is no longer straightforward to finance the auteur-driven fare that might catch the Cannes, Venice or TIFF Platform programmers’ eyes, even if those films come with lower price tags — something also suggested by the BFI’s report.

“It isn’t that Cannes or Venice don’t want to programme UK films,” says Palfrey. “But the routes to making those kind of films in the UK are narrowing. The question is, what can be done to support those more arthouse filmmakers?”

Audience dynamics

Another issue to contend with for UK producers is that coming out of the pandemic, audiences have been returning for tentpole US releases like Top Gun: Maverick and Minions: The Rise Of Gru but less so for independent or arthouse releases (although A24 had notable success in the UK with Everything Everywhere All At Once).

“When you look at the kind of festival offerings coming out from the UK and Ireland this year, it points to what we all know — there’s a huge amount of creative talent and filmmaking ability coming out of the system,” says Kevin Loader, also a producer on Pathé’s Allelujah. “There’s no shortage of ambition and storytelling skill [but] it’s going to come down in the end to how the distribution and exhibition sector recovers from the pandemic.”

McCracken echoes that point, noting the “core audience” for films like The Lost King and Allelujah is older, upscale, over 45 and “female skewing” — and so far they have not returned in great enough numbers. “There is a certain group-think that this audience is not going to come back to the cinemas, at least not in pre-pandemic numbers, and therefore the value placed on my films is much reduced,” McCracken says.

Roger Michell’s The Duke — which premiered at Venice 2020 but did not reach UK cinemas until February 2022 — grossed $6.1m (£5.3m) at the UK and Ireland box office. This was hailed as a strong result in the circumstances but Pathé’s expectations had been for at least $8.1m (£7m). “For me, that was a result which didn’t quite work,” says McCracken, noting the film’s release had to be delayed significantly due to the pandemic. “Part of the reason for that was because it felt old to people and therefore wasn’t part of the awards conversation.” (Despite industry goodwill towards the late Michell, his last dramatic feature failed to earn a single Bafta nomination.)

McCracken is confident this older audience can eventually be brought back to cinemas. In the short term, though, he is walking a tightrope. With The Lost King, for example, there are still territories to be sold.

“It has been broadly sold in all the principal European territories but I still have to sell Latin America, southeast Asia and eastern Europe… and if I don’t sell them, then I have a commercial problem,” he says. “If the film doesn’t work in the UK to the level I need it to work because that older audience isn’t coming back, then that becomes an economic problem.

“Allelujah I have sold a couple of territories very well but basically that is unsold,” he continues. “That’s why it has to be in Toronto in a prime slot to generate that interest in the expectation of sales.”

Allelujah was always intended as a theatrical film that could prove itself with UK cinema audiences (it is scheduled for release on February 17, 2023, two days before the Bafta Film Awards ceremony). According to Loader, it was “just about viable” on a $7m-$8m (£6m-£7m) budget but would not have been at a higher rate. “Sure, we could have gone to a streamer and they would have given us more money to make the film but that wouldn’t have put it in the same arena of connection with an audience,” he says.

Tempo Productions’ Piers Tempest talks of his struggles to finance Emily, which marks the directing debut of Frances O’Connor and was filmed in Yorkshire last year. Despite O’Connor being an experienced actress with credits ranging from Steven Spielberg’s AI: Artificial Intelligence to John Woo’s Windtalkers, Tempest says the UK’s public funders — the BFI, BBC Film and Film4, which form a crucial part of the UK’s independent production ecosystem — were wary about backing such an ambitious project from a first-time filmmaker. “Luckily, it was strong relationships with [financier] Ingenious, Warner Bros and [sales agent and financier] Embankment that got us through it,” Tempest says.

Projects like Emily are increasingly difficult to get made because of the streamer-fuelled rise in production costs, with technicians often tied into long-term contracts that leave them unable to work on smaller, independent features, and talent and soundstages also under lock and key. “We have a slate of brilliant projects but locking in talent on an indie budget is becoming harder and harder, because so many are locked into high-paying US shows with long commitments,” says Palfrey.

At the same time, the streamers remain among the most important buyers for UK independent fare in a period when theatrical distribution is struggling. Tempest has sold several of his recent titles to the VoD players. For example, romantic comedy Love Wedding Repeat, directed by Dean Craig, was acquired by Netflix for the world while Craig’s The Honeymoon was picked up by Amazon (in a deal brokered by WME). Meanwhile, Netflix UK pre-bought Tempo’s Bank Of Dave starring Hugh Bonneville and Rory Kinnear.

Palfrey also credits the backing of Amazon and Netflix with allowing her and other UK producers to broaden the scope of their projects. “Streamer or studio investment gives that bigger scale of production, which is important if you want a film to be seen widely,” she says. “The content boom has given us a new route to finance films at a level that wouldn’t be possible in the indie space, as was the case with My Policeman.”

An Amazon Original production, My Policeman is receiving a limited theatrical release in the UK and US from October 21 before landing globally on Prime Video on November 4. Palfrey, though, is hopeful some cinemas will continue to programme the film even after it becomes available online. She cautions, though, that it is dangerous for the UK independent production sector to become entirely dependent on streamers. “Some films just don’t suit the streamer model. Some of our most successful films as a company [Independent] — whether it’s We Need To Talk About Kevin, Moon or Carol Morley’s films — probably wouldn’t suit that model.”

Benign commissions

Christine Langan of Bonnie Productions, producer of The Lost King, points out that UK indie producers have traditionally been used to a “benign” commissioning environment working with BBC Film and Film4, which have long been incubators for new UK filmmaking talent (titles backed in recent years include Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun and Georgia Oakley’s Blue Jean for BBC Film and Rose Glass’s Saint Maud and Jim Archer’s Brian And Charles for Film4). But these bodies’ parent broadcasters, BBC and Channel 4, have come under pressure from a UK government led by the Conservative party that wants to scrap the licence fee of the former and privatise the latter; either outcome could have knock-on effects for these vital film-funding outposts, which Langan describes as “the UK’s secret weapon in nurturing and launching new British talent”.

Tempest makes the related point that “it’s in everyone’s interest” — including the US studios and streamers — to have a thriving UK independent production sector. The BFI’s report recommends such measures as increased tax relief support for independent filmmakers and an obligation for streaming services to support smaller UK films. Producers themselves suggest various remedies.

“We need to look at how theatrical may become more of a promotional activity,” says Ed Guiney of Element Pictures, which produced Hogg’s The Eternal Daughter, Lelio’s The Wonder and also operates arthouse cinemas in Ireland. Guiney suggests the theatrical release should become the equivalent of the hardback book in publishing, with the film eventually reaching its most significant audience on VoD.

“Public funders could look at how you support short runs theatrically in order to enhance the visibility of a film when it hits the digital home entertainment hub,” he says.

Others, though, continue to emphasise the primary importance of the big screen. “I believe in cinema and I believe that’s where the best experience of the films I make is going to be,” says McCracken.

While the sector is facing challenges, the producers with films at TIFF do not want to sound too downbeat. “We are blessed to have a stable tax credit and a country that talent want to come and work with. That’s why we’re busy,” says Tempest.

“These are films made by UK producers or companies that will hopefully be shown in UK cinemas, and we should celebrate that,” adds Palfrey.

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet