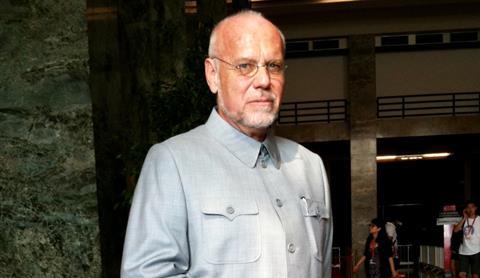

Marco Mueller, general advisor to the Beijing International Film Festival, talks to Liz Shackleton about Chinese audiences, censorship and positioning the fledgling festival as a bridge between the China market and the rest of the world.

A few weeks after completing his contract at the Rome Film Festival in December 2014, Marco Mueller was appointed as general advisor to the Beijing International Film Festival, launched by the Beijing city government in 2011.

A fluent Mandarin speaker who first visited China during the Cultural Revolution, Mueller had long been expected to move to one of the country’s fledgling festivals.

Together with his programming team, including international experts such as Alena Shumakova, Marie-Pierre Duhamel, Deepti D’Cunha and Paolo Bertolin, Mueller has pulled together a selection of 15 competition films and four galas, all of which are world or international premieres.

However, as Mueller explained to Screen International, his new role extends way beyond programming to also help position the festival as a world-class event with links into the global film market.

The fifth edition of the BJIFF kicks off tonight (April 16) with an opening ceremony at Huairou Yanqi Lake convention centre, while opening film, Paolo and Vittorio Taviani’s Maraviglioso Boccaccio, screens tomorrow night at the festival’s new home, the Oriental Theatre in central Beijing. Luc Besson heads the jury for the Tiantan competition.

What exactly is your role at BJIFF?

The Beijing municipal department that takes care of the festival was adamant that the

festival president should be the minister and the director is the city mayor. So they asked me to choose a title. General advisor sounds empty but has a concrete meaning in that I’m not just the artistic director, overseeing the international selection, but also advising them on how to run the festival.

This means first of all that the festival has an official selection for the first time. We have a very clear-cut distinction between Panorama, new directors, documentary, all the sidebars, and the official selection – the competition and gala titles – which must be world or international premieres.

I was also able to convince the authorities that it was necessary to decide once and for all on the main festival venue for this year and years to come. Then I realised that the seating capacity of the best Beijing theatres is very small. So we agreed to refurbish the Oriental Theatre, which has 1,200 seats and is a beautiful hall.

How long are you locked in for?

I asked that this 2015 edition should be a test year for both sides. We will have a two-day seminar at the end where we will invite some international experts and discuss the future of the festival. The key question would be the dates as it’s too close to Cannes and doesn’t translate into attractive dates for Chinese releases.

What kind of audience does the festival attract? And what is your programming strategy?

The student audience must become the core audience for this festival – they are the ones who will grow into professionals and be able to afford to buy movie tickets in the future. They are also the best test audience for sales companies who would then come and use Beijing as a platform to understand what can and cannot work with various groups of viewers in China.

The best testimony to that angle is that MK2 agreed to move the international premiere of the Taviani brothers’ film to Beijing.

I was also given the precise instruction – please don’t try to select two films from the same country. That geographical diversity is also important to the festival as it proves it can appeal to the international arena.

Why select Maraviglioso Boccaccio as the opening film?

With this film you have two old masters of cinema adapting a known literary work, that is also known in China, but trying to use the past as a comment on the present. At the same time, they wanted to make a popular film, so delivered a lavish costume spectacle, and you have to think of the number of costume dramas that have been huge box office hits in this country.

How does the BJIFF selection process work?

We didn’t have to go through first the three levels of the selection committee. We went directly to the executive committee and submitted a selection of almost 40 titles for the official selection, knowing that this would be reduced to 20 titles. There was a very frank discussion and we were told that even short but graphic depictions of sex cannot pass censorship. But when it came to thematic boldness, it was a positive surprise to see that there is a wide range of subjects that can be accepted.

Does China have the same censorship regulations for festival titles and theatrical releases?

Entirely the same and I think that is healthy, otherwise you may have a huge festival success and the film could not be distributed. And the same kind of censorship applies to both theatrical releases and VOD platforms, so you always have the possibility of selling to VOD.

Do you also have input into the Beijing Film Market?

The festival and market are still run as separate entities, but if there is any possibility of growth for this festival, it would have to be on the condition that all the key buyers from East Asia are present at the market. In the past, the market didn’t include the key Japanese, Korean or Indonesian buyers – so why would a producer or sales agent gamble on a Beijing presentation? That has to change for it to become a world-class festival and the main pole of attraction in Asia.

What lessons did you learn during your time at Rome film festival that you can apply here?

To believe that you can grow your own very special audience, and not just be resigned to the concept of an unchangeable target audience. You could see that in the audience awards at last year’s Rome festival – a very special English-language film [Stephen Daldry’s Trash], an Italian comedy [Roan Johnson’s Fino A Qui Tutto Bene] that confounded expectations of what kind of comedies work in Italy; and two Asian films [Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider and Xu Ang’s 12 Citizens].

Working at Italian film festivals you must have encountered political issues and the ‘old guard’ in the city governments. Is it the same here in Beijing?

The very precise political context in Italy now makes it impossible for somebody who doesn’t strike a political alliance to move freely and realise his vision. I was happy to find here that you can be a foreigner without any clear political affiliation and still be able, not only to work, but to inject a totally new way of doing things.

It can still be complicated, but this is a five-year-old festival, and nobody has ever told me ‘but we’ve always done things this way’. What I might hear is ‘we’ve never done this before’. But if you’re patient enough, you can explain yourself and sometimes it really works.

Any other differences between working for European and Chinese film festivals?

The main difference is that – very sadly for me as a European – there is no longer much of an Italian market and here the market is growing and trying out new channels of distribution. Also the level of technological advancement here is such that we can really experiment. Of course you have to adjust all the time, but I really feel like you’re in a place where everything is going to move very rapidly. Whereas Italy has become a market only for American and Italian-language films.

But isn’t the market here focused on Hollywood and Chinese-language films?

Yes, but there will be change. The authorities here are very serious about creating a “prestige” film circuit. That is why I wanted to experiment with new Latin American directors and to see how their films would fare with Chinese student audiences. There is no awareness or excitement for Latin America right now in China, but the next group of emerging realities, both financially and artistically, is going to come from Latin American countries.

No comments yet