David Pantaleón’s Our Father (Rendir Los Machos) opened the New Waves section at this week’s Seville European Film Festival (November 5-13).

Canary Islands-born Pantaleón began his career as an actor before he began to directing short films including The Painted Calf and The Passion of Judas, which screened at multiple film festivals.

His debut feature is a co-production between Spain’s Volcano Films, who had seen Pantaleon’s shorts and approached him to make a feature, and France’s Noodles Production. It grapples with issues of patriarchy and male identity and tells the story of two brothers who have to cross the island of Fuerteventura on foot to offer a bunch of male goats their dead father has donated in his will to a man they hardly know. Their sister is excluded from the ritual and oversees it at a distance.

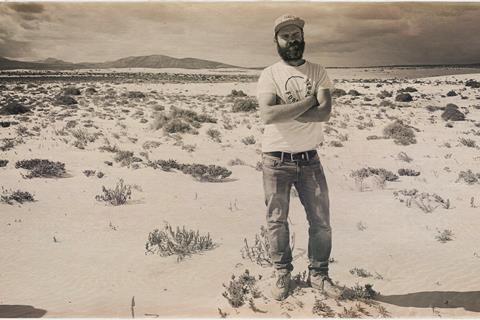

Pantaleon talks to Screen about inverting the tropes of American westerns to capture a landscape that manages to shrink both the men and their troubles,

What was your inspiration for the film? Is there any truth to the local tradition about male heirs having to give away part of their goat herd?

No, no [laughs], we made it up as a way of pointing out that traditions are the result of fiction, that they have been made up. Traditions are such a strange world. You’ll find that the weirdest narrative you can come up with can be a tradition somewhere in the world. So, why not make something like this up? Identity is built on tradition and tradition is a result of certain narratives. I found that quite fascinating.

Why did you want explore the concept of masculinity?

Masculinity is another created narrative and here I wanted to convey how infantile it can get, the conflict between appearances and reality embodied by the shepherds in the story.

Can you talk about playing with the classic themes of both the western and the road movie? You don’t show men on horses, instead they walk on foot and often look tiny, framed by a grand landscape in stunning visual compositions by DoP Cristina XX

The landscape and its transformation, patriarchy, masculinity, the frontier, living of the land, a sense of a vanishing world, are all topics present in the western as they are in our film, but we deal with a very absurd conflict, nothing grand, epic.

We have two brothers that have fallen out but we never know exactly why. They also look so alike that you get confused with who is who, making it impossible to take sides. The world of the goat farmers in Fuerteventura offered a very specific iconography, not of cowboys but of shepherds. There’s a saying that calls the goat ‘the cow of the poor’. These animals are resilient enough to live in a tough Fuerteventura landscape and are part of it.

As for the men, we often observe them with overhead aerial shots, as from the eye of an all-mighty presence that we called “God’s tripod”. It also gives the film a timeless touch. We shot mainly inland which is the part of the island where people never go. Tourists stay on the beach. Maybe because of my theatrical background I tend to see the frame as a stage, and we very rarely use camera moves.

What was the hardest part of the shoot?

Finding the seven male goats. That in itself could be a film. We had to bring them from outside the islands because the ones from Fuerteventura are so strong and stubborn that they would have been impossible to control. The goat whisperer worked with the seven goats for a month and the actors learned to handle them too because they had no idea of how to do that. But I’ll confess I wasn’t quite sure it would work when we started to shoot. Something that worried me too was being able to keep the energy and team spirit of a long shoot since I had only done shorts beforehand. But I’m happy to say it went well. We managed the long-distance run.

No comments yet